On December 25, 1956, a baby was born in Germany with arms that looked like flippers - no hands, no elbows, just stumps. No one knew why. That baby was the first known victim of thalidomide, a drug sold as a harmless sleep aid and cure for morning sickness. By the time doctors connected the dots, over 10,000 children worldwide had been born with severe birth defects. Many didn’t survive their first year. Others lived with missing limbs, deafness, blindness, or internal organ damage. It wasn’t a natural disaster. It was a medical failure - one that changed how every drug is tested today.

What Thalidomide Was Supposed to Do

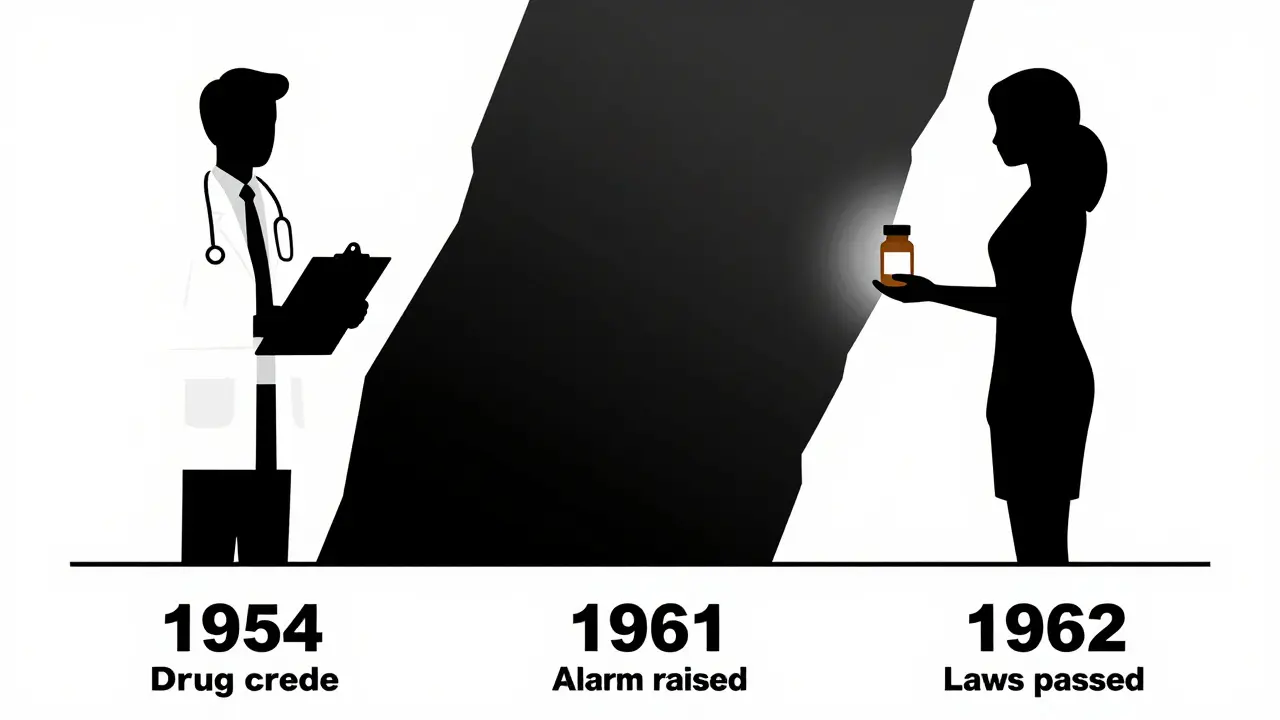

Thalidomide was created in 1954 by a German pharmaceutical company, Chemie Grünenthal. It was marketed as safe, non-addictive, and gentle - perfect for pregnant women suffering from nausea. By 1958, it was sold in 46 countries under dozens of brand names. In the UK, it was called Distaval. In Canada, it was Thalomid. Doctors trusted it. Nurses handed it out. Women took it without question. It was everywhere.

But here’s the thing: no one tested it properly for use in pregnancy. Animal studies were shallow. Human trials were limited. The assumption was that if it was safe for adults, it was safe for unborn babies. That belief was wrong - catastrophically wrong.

The Teratogenic Window: When It Was Too Late

The damage didn’t happen because a woman took the drug for weeks. It happened because she took it for just a few days - between the 34th and 49th day after her last period. That’s about five to seven weeks into pregnancy. By then, the baby’s limbs, ears, eyes, heart, and internal organs were forming. Thalidomide didn’t cause random damage. It targeted specific stages of development.

One dose during that window could mean a child born without arms or legs - a condition called phocomelia. Others had facial paralysis, missing eyes, or holes in their heart. Some had no esophagus, no appendix, no gallbladder. The UK’s 1964 government report said almost every organ system could be affected. And the worst part? The mother often felt fine. No vomiting, no dizziness, no warning. Just a quiet, devastating change in the womb.

Who Stopped It - And Who Didn’t

Two doctors, working independently on opposite sides of the world, were the first to sound the alarm. In Australia, Dr. William McBride noticed a spike in babies born with limb defects. He wrote a letter to The Lancet in June 1961, linking them to thalidomide. In Germany, Dr. Widukind Lenz, a pediatrician, had been collecting cases for months. He called Grünenthal on November 15, 1961, and said: “This drug is killing babies.”

Germany pulled it off shelves on November 27. The UK followed on December 2. But in the United States, it never got far. A young FDA reviewer named Frances Oldham Kelsey refused to approve it. She asked for more data on how it crossed the placenta. Her bosses pressured her. The drug company pushed back. She held firm. Because of her, the U.S. avoided the worst of the tragedy. Today, she’s remembered as the woman who saved thousands of American babies.

The Aftermath: How the World Changed

The fallout was immediate. Public outrage. Lawsuits. Media storms. But the real change came in the rules.

In 1962, the U.S. passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendments. For the first time, drug companies had to prove their products were not just safe - but effective. They had to test for birth defects. They had to report side effects. Clinical trials became stricter. The UK created the Committee on the Safety of Medicines. Other countries followed. Teratogenicity testing became standard.

Before thalidomide, a drug could be sold with almost no proof it worked. Afterward, every new medicine had to go through a gauntlet of tests - especially if it might be used by women who could get pregnant.

Thalidomide’s Second Life

Here’s the twist: thalidomide didn’t disappear. It came back.

In 1964, a doctor in Peru named Jacob Sheskin tried giving it to a leprosy patient with painful skin sores. The sores cleared up. He didn’t know why. But it worked. Decades later, scientists discovered thalidomide blocks new blood vessel growth - a process called angiogenesis. Tumors need blood vessels to grow. So did developing limbs. That’s why it caused birth defects - and why it could kill cancer.

In 1998, the FDA approved it for leprosy-related skin sores. In 2006, it got approval for multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer. In clinical trials, patients on thalidomide lived longer. Their cancer progressed slower. But the side effects were brutal: nerve damage, extreme fatigue, dizziness. Up to 60% of patients had to stop taking it.

Still, it worked. And that’s why it’s still used today - but under strict control.

How It’s Used Now: The STEPS Program

Today, thalidomide is one of the most tightly controlled drugs in the world. The U.S. has the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS). It’s not just a form you sign. It’s a whole system.

- Women of childbearing age must take two forms of birth control.

- They must have a negative pregnancy test every month.

- They can’t share the drug with anyone.

- Doctors must be certified to prescribe it.

- Pharmacies can only dispense it through registered suppliers.

The message is clear: this drug can still cause devastating birth defects. Even one pill. Even if you’re not pregnant - but might become pregnant. The risk hasn’t gone away. The science just caught up.

What We Learned - And What We Still Forget

Thalidomide taught us that drugs don’t just affect the person taking them. They affect the unborn. They affect families. They affect generations.

It also showed us that science can be slow. That doctors trust too easily. That companies prioritize profit over safety. And that sometimes, the only thing standing between a drug and disaster is one cautious person who says, “Wait.”

Today, new drugs are tested for teratogenicity. But we still see problems. Opioids during pregnancy. Antidepressants. Seizure medications. We assume they’re safe because they’re prescribed. But we don’t always ask: What happens if a woman gets pregnant while taking this?

Thalidomide’s legacy isn’t just in the laws. It’s in the questions we should always ask.

Why This Matters for Pregnant Women Today

If you’re pregnant, or thinking about getting pregnant, here’s what you need to know:

- Never take any new medication without checking with your doctor - even if it’s “just a vitamin” or “over-the-counter.”

- Some common drugs - like isotretinoin (for acne), lithium (for bipolar disorder), or certain anticonvulsants - are known to cause birth defects.

- Ask: “Is this safe in pregnancy?” Don’t settle for “I’ve never heard of a problem.”

- Keep a list of everything you’re taking - supplements, herbs, creams - and review it with your provider at every visit.

Thalidomide was a one-time disaster. But the mindset that caused it? That’s still out there. The lesson isn’t just history. It’s a warning.

The Science Behind the Damage

In 2018 - 60 years after the first baby was born with phocomelia - scientists finally figured out how thalidomide broke developing limbs. It binds to a protein called cereblon. That protein normally helps control which genes turn on during early development. Thalidomide hijacks it. Instead of building arms and legs, the embryo’s cells start destroying the very proteins needed to form them.

That’s why it’s so dangerous: it doesn’t poison. It rewires development. And it only does it during a narrow window. That’s also why it works against cancer: in tumors, it does the same thing - knocks out proteins cancer cells need to survive.

The same mechanism that caused tragedy now saves lives. That’s the cruel irony of thalidomide. And that’s why we can’t just ban it. We have to control it.

Where to Learn More

The Science Museum in London has a permanent exhibit on the thalidomide tragedy. It includes real medical records, baby clothes, and personal stories. Medical schools around the world still teach it as a case study. It’s not just about drugs. It’s about ethics. Responsibility. And the cost of complacency.

There are still survivors - now in their 60s and 70s - who fight for better care, better compensation, and better awareness. Their voices remind us: this wasn’t just a medical mistake. It was a human one.

Can thalidomide still cause birth defects today?

Yes. Even a single dose of thalidomide during early pregnancy can cause severe birth defects. That’s why it’s only prescribed under strict programs like STEPS, which require monthly pregnancy tests and two forms of birth control for women of childbearing age. The risk hasn’t changed - only the safeguards have.

Is thalidomide used for anything besides cancer and leprosy?

It’s sometimes used off-label for other conditions like lupus, HIV-related wasting, and severe mouth ulcers. But because of the risks, these uses are rare and only considered when other treatments have failed. No new approvals are being made without strong evidence and strict controls.

What are the most common birth defects linked to thalidomide?

The most common are limb malformations, especially phocomelia - where arms or legs are shortened or missing. Other defects include missing ears or eyes, facial paralysis, heart problems, and abnormalities in the digestive tract like a blocked esophagus or anus. Some babies had no appendix or gallbladder at all.

Why didn’t animal testing catch the danger earlier?

Because the way thalidomide affects embryos is species-specific. It causes birth defects in humans and certain primates - but not in rats, mice, or rabbits, which were the animals used in early tests. That’s why scientists didn’t see the danger until babies were born with defects. Today, we test on multiple species, including primates, to avoid this mistake.

Are there safer alternatives to thalidomide for cancer treatment?

Yes. Drugs like lenalidomide and pomalidomide were developed as safer versions. They work similarly but have lower risks of nerve damage and are less likely to cause birth defects - though they still require pregnancy prevention programs. They’re now preferred over thalidomide in most cases.

Can men taking thalidomide affect their unborn children?

Yes. Thalidomide can be present in semen. Men taking it are advised to use condoms during sex, even if their partner can’t get pregnant. This is part of the STEPS program. The drug can damage sperm DNA, and there have been rare cases of birth defects linked to paternal use.

Is thalidomide still sold in New Zealand?

Yes, but only under strict government controls. It’s approved for leprosy and multiple myeloma, and prescribing follows international safety guidelines. Pharmacists must be trained, and patients must sign consent forms confirming they understand the risks. It’s not available over the counter or through online pharmacies.

How do I know if a medication is safe during pregnancy?

Always check with your doctor or pharmacist. Don’t rely on internet searches or old advice. The FDA and other health agencies classify drugs by pregnancy risk categories (A, B, C, D, X). Category X means it’s known to cause birth defects - like thalidomide. Even Category B drugs should be reviewed carefully. When in doubt, pause and ask.

Susie Deer

This is why we need to stop letting big pharma run wild. One pill. One mistake. Thousands of lives ruined. No excuses.

TooAfraid ToSay

Wait wait wait-so you're telling me the SAME drug that maimed babies is now used to treat CANCER? That’s not science, that’s a horror movie plot.

Robert Way

i think the real problem is people trust doctors too much. i took benadryl while pregnant and my kid is fine. so maybe thalidomide was just bad luck?

Vicky Zhang

Oh honey. I just want to hug every single woman who went through this. And every doctor who stood up and said ‘no’ when everyone else said ‘yes’. This story? It’s not just history. It’s a love letter to caution. To listening. To saying ‘I don’t know’ when you should. You’re not weak for asking. You’re brave.

Allison Deming

The systemic failure here is not merely institutional-it is moral. The commodification of human life under the guise of pharmaceutical progress constitutes an ethical abdication of the highest order. One must ask: when does profit become predation?

shiv singh

you think this was bad? wait till you hear about the 500k kids who got autism from vaccines. same thing. they just hide it better now. they dont want you to know the truth.

says haze

The irony is not merely poetic-it’s ontological. Thalidomide didn’t cause malformations; it revealed the fragility of biological determinism. The same molecular mechanism that disrupts limb morphogenesis now targets angiogenic pathways in neoplasms. It’s not a drug. It’s a mirror. And we’re still afraid to look.

Alvin Bregman

i just think its wild that a drug that hurt so many can now help people live longer. kinda makes you wonder what else weve been wrong about. maybe we should be more careful but also less scared

Sarah -Jane Vincent

I’ve got news for you. Thalidomide was never banned. It was just hidden. The government and the drug companies made a deal. They let it come back under a new name with a fancy program so you’d think they fixed it. But they didn’t. They just made it harder to trace. Wake up.

Henry Sy

man i read this and i just wanna scream. not because of the science, but because of the mothers. imagine holding your baby with no arms and knowing you gave it to them by accident. that’s not a tragedy. that’s a crime. and the people who sold it? they got rich. while those kids cried in silence.

Anna Hunger

The implementation of the STEPS program represents a paradigmatic shift in pharmacovigilance, establishing a robust framework for risk mitigation grounded in procedural rigor, informed consent, and interprofessional accountability. This model ought to be extended to all teratogenic agents.

Jason Yan

I think the real lesson here isn’t just about drugs or science. It’s about listening. About humility. That one doctor in the US who said ‘wait’? She didn’t have all the answers. She just had the courage to pause. And that’s something we’ve forgotten. We rush. We assume. We trust too fast. We need more pauses.

Sarah Triphahn

You people are being naive. This isn’t about safety. It’s about control. The system needs a villain to justify its power. Thalidomide was convenient. Now they use it to scare you into taking their new drugs. Same game. New label.