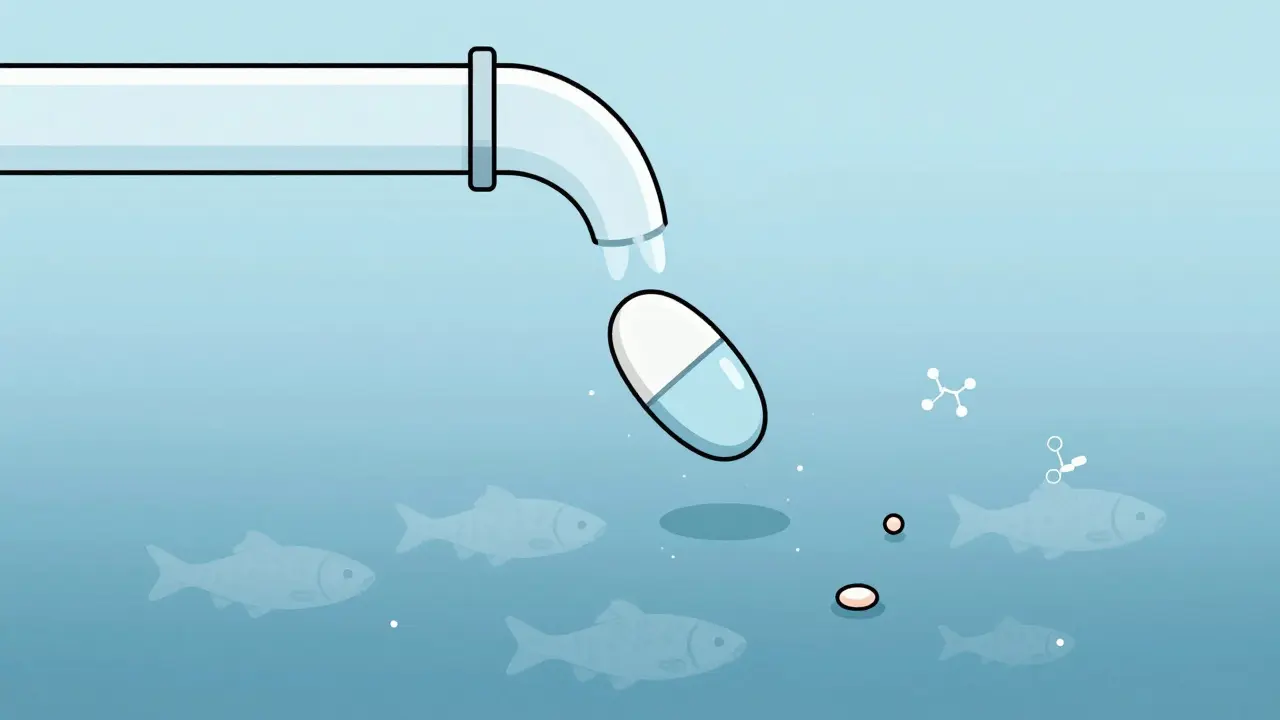

Every year, millions of unused pills, liquids, and patches end up in toilets and trash cans across the world. Many people think flushing old medications is the safest way to get rid of them-especially if they’re expired or no longer needed. But here’s the truth: flushing medications is one of the worst things you can do for your local waterways, wildlife, and even your own drinking water.

Why Flushing Medications Hurts the Environment

When you flush a pill down the toilet, it doesn’t disappear. It enters the wastewater system, where most treatment plants aren’t designed to remove pharmaceutical chemicals. These plants clean out solids, bacteria, and dirt-but they can’t filter out tiny drug molecules. That means antibiotics, painkillers, antidepressants, and hormones end up flowing into rivers, lakes, and even groundwater that feeds into drinking water supplies. Studies from the U.S. Geological Survey in the early 2000s found traces of over 80 different pharmaceuticals in 80% of tested waterways across the U.S. Even today, these compounds show up globally. In New Zealand, similar patterns have been detected in urban waterways near wastewater outlets. Concentrations are low-often below 100 nanograms per liter-but that’s enough to cause real harm. Fish in contaminated waters have shown abnormal development: male fish producing eggs, reduced fertility, and altered behavior. These changes are linked to estrogen-like compounds from birth control pills and hormone therapies. NSAIDs like ibuprofen and diclofenac, commonly found in household medicine cabinets, have been shown to damage fish kidneys and gills. Even small amounts of antibiotics in water contribute to the rise of drug-resistant bacteria, a growing global health threat.What Happens When You Throw Medications in the Trash?

Some people think tossing pills in the garbage is better than flushing them. It’s a common assumption-but it’s not much better. When medications go to landfills, rain and groundwater can wash them out, creating toxic leachate that seeps into soil and aquifers. One study found acetaminophen levels in landfill leachate as high as 117,000 ng/L-over a thousand times higher than what’s found in treated wastewater. Plus, there’s another risk: pets, kids, or even wildlife might dig through trash and accidentally ingest pills. This is especially dangerous with opioids, sedatives, or psychiatric medications. The DEA estimates that nearly half of people who misuse prescription drugs get them from family or friends’ medicine cabinets.The FDA’s ‘Flush List’-What’s Really Safe?

You might have heard that some medications are okay to flush. That’s because the FDA maintains a short list of drugs considered dangerous enough to justify flushing-mostly powerful opioids like fentanyl patches and oxycodone tablets. These drugs can be deadly if found by children or stolen for misuse. In those rare cases, flushing is the fastest way to remove them from homes. But here’s the catch: this list only includes about 15 medications out of thousands. Most common drugs-like blood pressure pills, antibiotics, or cholesterol meds-are NOT on the list. Flushing them does more harm than good. And many people don’t know the difference. A 2021 FDA survey found that only 30% of Americans could correctly identify which medications should or shouldn’t be flushed.

The Best Alternative: Take-Back Programs

The most effective, science-backed solution is medication take-back programs. These are drop-off locations-usually at pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations-where you can safely return unused or expired drugs. The medications are collected and incinerated under strict environmental controls, preventing any release into water or soil. In the U.S., the Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 made it legal for pharmacies to run these programs. As of 2023, there were just over 2,140 authorized collection sites nationwide-and most are in cities. Rural areas are still underserved. In New Zealand, take-back options are limited but growing, with some pharmacies and district health boards offering seasonal collection events. Even if you live far from a drop-off site, don’t give up. Many communities hold annual drug take-back days, often coordinated with the DEA or local health departments. Check your city or regional council website-these events are usually free and anonymous.What to Do If There’s No Take-Back Option

If you can’t get to a collection site and don’t want to flush or toss your meds, the EPA recommends this method:- Take the pills out of their original containers.

- Mix them with something unappetizing-used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt.

- Put the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or container.

- Throw it in the trash.

Why Prevention Is the Real Solution

The best way to reduce pharmaceutical pollution? Don’t generate it in the first place. Many people stockpile medications because they’re afraid they’ll need them again-or they don’t know when they expire. But most drugs remain effective for years past their labeled date. The FDA says only a small number lose potency quickly, and even then, they’re usually still safe. Talk to your pharmacist before buying large quantities. Ask if you can get smaller packs. Some clinics now offer “just enough” prescriptions for short-term use. In Europe, countries like Germany and Sweden have started requiring pharmacies to offer take-back services by law. California passed a law in 2024 requiring all pharmacies to include disposal instructions with every prescription. Pharmaceutical companies are also being held more accountable. The European Union now requires new drugs to undergo environmental risk assessments before approval. Some manufacturers are exploring biodegradable packaging and return-incentive programs.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for policy changes to make a difference. Here’s what you can do right now:- Check your medicine cabinet. Pull out anything expired, unused, or no longer needed.

- Look up your local take-back program. Search “[Your City] medication disposal” or contact your pharmacy.

- If no drop-off is available, use the coffee grounds method.

- Don’t flush anything unless it’s on the FDA’s official flush list.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist about prescribing only what you’ll actually use.

How Long Do These Chemicals Last?

Some pharmaceutical compounds don’t break down easily. For example, carbamazepine (used for epilepsy) can persist in water for years. Others transform into new chemicals after treatment-sometimes more toxic than the original. This is why simply waiting for nature to clean it up doesn’t work. Advanced water treatment technologies like ozone filtration and activated carbon can remove 85-95% of these compounds, but they’re expensive. Retrofitting a single wastewater plant can cost between $500,000 and $2 million. That’s why prevention and proper disposal remain the most practical solutions.Final Thought: It’s Not About Perfection

You won’t stop all pharmaceutical pollution by yourself. But you can stop contributing to it. Every pill you return instead of flush, every conversation you have with a friend about safe disposal, every time you ask for a smaller prescription-you’re part of the solution. The goal isn’t to be perfect. It’s to be better than yesterday.Is it ever okay to flush medications?

Yes-but only for a very small list of drugs the FDA specifically designates as dangerous if misused, like fentanyl patches or certain opioids. These are rare exceptions. For 99% of medications, flushing is harmful and unnecessary. Always check the FDA’s current flush list before doing so.

Can I recycle empty medicine bottles?

Yes, most plastic medicine bottles are recyclable. But first, remove or scratch out all personal information on the label. Then rinse the bottle and check your local recycling rules-some programs require removing the cap, others don’t. If you’re unsure, it’s safer to throw the bottle in the trash than risk privacy breaches.

Why don’t more pharmacies offer take-back programs?

Cost and logistics. Running a take-back program requires storage, security, and coordination with hazardous waste handlers. Many pharmacies, especially small ones, lack funding or space. Government support and manufacturer funding (like in the EU) help, but in places like the U.S., these programs are still patchy and underfunded.

Do expiration dates mean I have to throw pills away?

Not always. Most medications remain safe and effective well past their expiration date. The FDA says only a few lose potency quickly, like nitroglycerin or insulin. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist. Holding onto unused meds increases the chance they’ll end up flushed or misused.

Are there any at-home devices that destroy medications safely?

Yes, products like Drug Buster or MedTakeBack use chemical deactivation to neutralize pills. But they’re expensive ($30+ per unit), require precise use, and aren’t widely available. For most people, the EPA’s coffee grounds method is simpler, cheaper, and just as effective for preventing misuse and reducing environmental harm.

What’s the biggest barrier to proper medication disposal?

Lack of awareness and access. Many people don’t know flushing is harmful. Others live too far from drop-off sites. Surveys show only 30% of U.S. residents know where to return medications. Fixing this means better education, more collection points, and clearer labeling on prescription bottles.

Sandeep Jain

bro i just flush my old pills cause its easy and no one tells u this is bad till u read somethin like this. mind blown.

sakshi nagpal

Thank you for this detailed post. In India, we rarely have access to take-back programs, so I’ve started mixing my expired meds with used coffee grounds and sealing them in plastic before disposal. It’s a small step, but I feel better knowing I’m not poisoning our rivers. More awareness is desperately needed.

roger dalomba

Wow. A post that doesn’t suck. Who knew environmental responsibility could be this… boringly correct?

Brittany Fuhs

Of course the FDA only lists 15 drugs. That’s because they’re too busy protecting Big Pharma profits. Meanwhile, Americans flush everything and blame the water. We’re not Europe, and we don’t need their socialist pill policies.

Becky Baker

my mom still flushes her blood pressure pills. she says 'it's just a few pills, what's the big deal?' i told her it's like saying 'it's just one cigarette.' she didn't talk to me for a week. worth it.

Rajni Jain

i used to toss meds in the trash till i saw a raccoon chewing on an old bottle in the alley. now i mix mine with cat litter and hide it deep. no one deserves to get hurt by someone else's old pills. thanks for reminding us.

Sumler Luu

It’s worth noting that the EPA’s coffee grounds method is not just practical-it’s empirically effective at deterring accidental ingestion. The physical barrier and olfactory deterrent significantly reduce retrieval risk. This is not anecdotal; it’s backed by landfill leachate studies.

Sophia Daniels

Oh my god. You mean we’re not supposed to just toss our antidepressants into the toilet like they’re last night’s sushi? I’m literally shaking. What’s next? Not dumping expired sunscreen in the ocean? I’m gonna need a therapist after this revelation.

Nikki Brown

And yet… people still flush. 😔 It’s not ignorance-it’s laziness wrapped in denial. We have the tools. We have the knowledge. We just don’t care enough until it’s our kid who gets sick from the water. Then it’s too late.

Peter sullen

Given the current regulatory architecture surrounding pharmaceutical waste management, it is imperative to recognize that decentralized, community-based take-back infrastructure-when properly resourced and federally incentivized-constitutes the only scalable, environmentally sound solution to mitigate bioaccumulative pharmaceutical effluents. Without systemic intervention, localized behavioral modifications remain statistically negligible in impact.