DPP-4 Inhibitor Pancreatitis Risk Calculator

This tool helps estimate your personal risk of pancreatitis while taking DPP-4 inhibitors (gliptins). It is not a substitute for medical advice and should be discussed with your healthcare provider.

When you’re managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing low glucose or weight gain feels like a win. That’s why DPP-4 inhibitors - also called gliptins - became so popular. Drugs like sitagliptin (a DPP-4 inhibitor used to treat type 2 diabetes by increasing insulin release and reducing glucagon, Januvia), saxagliptin (a DPP-4 inhibitor that enhances incretin activity, Onglyza), and linagliptin (a DPP-4 inhibitor with kidney-friendly excretion, Tradjenta) are still prescribed to millions worldwide. But behind the convenience of an oral pill that doesn’t cause hypoglycemia lies a quiet, serious risk: acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatitis Isn’t Just a Theoretical Risk - It’s Documented

It’s easy to dismiss warnings as rare side effects that won’t happen to you. But the data doesn’t lie. A 2024 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology found that patients taking DPP-4 inhibitors had a reporting odds ratio (ROR) of 13.2 for acute pancreatitis. That means the chance of reporting pancreatitis was over 13 times higher among users than in the general population. Even more telling, a meta-analysis of nearly 54,000 patients showed a 54% increased risk compared to placebo or other diabetes drugs. The absolute numbers might sound small - about 1 extra case per 834 patients over 2.4 years - but when you’re one of those patients, it’s not small. Acute pancreatitis isn’t a stomach bug. It’s sudden, severe abdominal pain that can radiate to your back, often requiring hospitalization. In 17.7% of reported cases, it led to serious complications like organ failure or infection. And while most cases improved after stopping the drug, some didn’t. The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) confirmed this risk back in 2012, and since then, every major regulator - the FDA, EMA, Health Canada - has updated labeling to include pancreatitis as a known side effect. This isn’t a rumor. It’s science.Why Does This Happen? The Science Is Still Unclear

Here’s the frustrating part: we don’t fully understand why DPP-4 inhibitors might trigger pancreatitis. These drugs work by blocking an enzyme called DPP-4, which breaks down incretin hormones like GLP-1. More GLP-1 means more insulin and less glucagon - great for blood sugar. But GLP-1 is also present in the pancreas, and its prolonged activity might affect pancreatic cells in ways we haven’t mapped out yet. Animal studies haven’t given clear answers. Some showed inflammation; others didn’t. Diabetes itself increases pancreatitis risk - people with the condition are already 2 to 3 times more likely to develop it than those without. So is the drug causing it, or just revealing an underlying vulnerability? The answer isn’t black and white. What we do know is that the risk isn’t the same across all DPP-4 inhibitors. Linagliptin showed a small but measurable increase in pancreatitis cases during clinical trials, even though it’s marketed as having a low drug interaction profile. Saxagliptin and alogliptin had higher numbers in large cardiovascular trials. Sitagliptin, the most widely used, has the most data - and still, the signal is there.How Do You Know If It’s Pancreatitis - And What Should You Do?

You won’t feel a little discomfort. Acute pancreatitis hits hard and fast:- Severe, constant pain in the upper abdomen - often described as a “boring” or “gnawing” sensation

- Pain that spreads to your back

- Nausea and vomiting that doesn’t improve

- Fever or rapid pulse

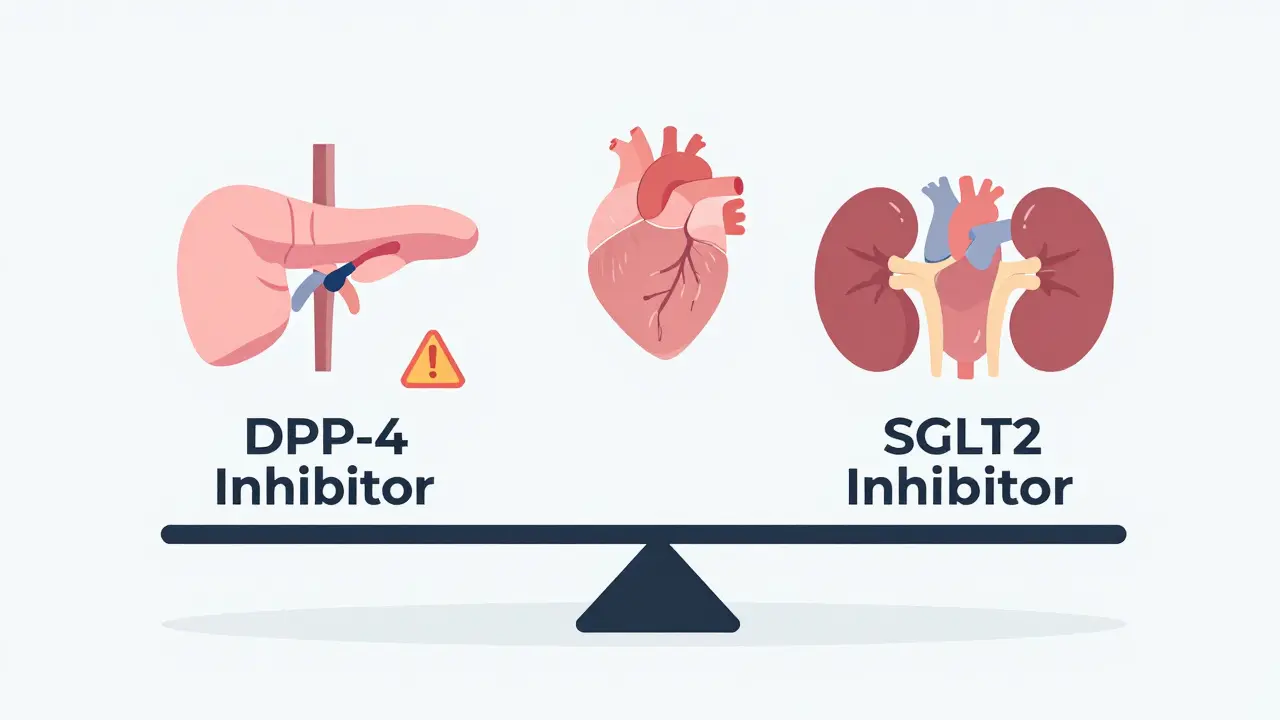

How Do DPP-4 Inhibitors Compare to Other Diabetes Drugs?

It’s not fair to look at DPP-4 inhibitors in isolation. You need context. Here’s how they stack up:| Drug Class | Pancreatitis Risk | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 inhibitors (gliptins) | High relative risk | ROR of 13.2; 1 in 834 patients over 2.4 years develops pancreatitis |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | Moderate risk | ROR of 9.65; liraglutide specifically linked to cases; injectable only |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Low risk | Significantly lower than DPP-4 inhibitors; may even reduce risk |

| Metformin | Very low risk | First-line treatment; no strong association with pancreatitis |

| Sulfonylureas | Low risk | Higher hypoglycemia risk; no pancreatitis signal |

Interestingly, SGLT2 inhibitors - newer drugs like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin - appear to have a lower pancreatitis rate than DPP-4 inhibitors. They also offer heart and kidney protection, which is why many doctors now prefer them for patients with cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease.

And while GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic) are trending for weight loss, they carry their own pancreatitis risk - just slightly lower than gliptins. So if you’re switching from a DPP-4 inhibitor to a GLP-1 agonist for weight control, you’re not necessarily eliminating the risk. You’re trading one for another.

Who Should Avoid DPP-4 Inhibitors?

Not everyone needs to avoid them. For most people, the benefits outweigh the risks. But certain patients should be extra cautious:- Those with a history of pancreatitis - even if it was years ago

- People with gallstones or high triglycerides

- Heavy alcohol users

- Patients with chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic duct abnormalities

- Anyone with unexplained abdominal pain or digestive issues

Why Are These Drugs Still Prescribed?

If the risk is real, why are DPP-4 inhibitors still on the market? Because they have real advantages:- No hypoglycemia - unlike sulfonylureas or insulin

- Weight neutral - unlike insulin or some older pills

- Oral form - easier than daily injections

- Good cardiovascular safety - unlike some older diabetes drugs

What Should You Do If You’re on a DPP-4 Inhibitor?

If you’re currently taking one, here’s what to do:- Know the symptoms of pancreatitis. Write them down. Share them with a family member.

- Don’t ignore persistent stomach pain. Even if it’s mild. Call your doctor.

- Ask your doctor if your current drug is still the best choice - especially if you have other risk factors.

- Don’t stop the drug suddenly without talking to your provider. Uncontrolled blood sugar is dangerous too.

- Report any suspected side effects. In the U.S., use the FDA’s MedWatch system. In the UK, use the Yellow Card scheme. Your report helps others.

What’s Next for DPP-4 Inhibitors?

Research is ongoing. Scientists are looking at genetic markers that might predict who’s more likely to develop pancreatitis on these drugs. A 2022 review in Current Diabetes Reports suggests future testing could one day identify high-risk patients before they even start treatment. Meanwhile, global sales of DPP-4 inhibitors hit $5.8 billion in 2022 - but growth is slowing. Newer drugs like GLP-1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors are taking market share because they offer more than just blood sugar control: they protect the heart, kidneys, and help with weight loss. The future of diabetes care isn’t just about lowering glucose. It’s about preventing complications - including rare but serious ones like pancreatitis. That’s why the conversation around DPP-4 inhibitors is shifting from “are they safe?” to “who are they safe for?”Can DPP-4 inhibitors cause pancreatic cancer?

No. Multiple large studies, including a meta-analysis of over 55,000 patients, found no increased risk of pancreatic cancer with DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists. The concern arose years ago due to early animal studies and case reports, but long-term human data has consistently shown no link. The FDA and EMA have both cleared these drugs of cancer risk.

Are there any DPP-4 inhibitors that are safer than others?

All DPP-4 inhibitors carry the same class-wide risk of pancreatitis. While linagliptin has a lower risk of drug interactions because it’s excreted mostly through the bile, its pancreatitis risk is still present. No gliptin is considered “safer” in this regard. The choice between them should be based on kidney function, cost, and other side effects - not pancreatitis risk.

What are the most common side effects of DPP-4 inhibitors?

Most people tolerate them well. Common side effects include headaches, stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, and mild stomach upset. These are usually temporary and mild. Serious side effects like pancreatitis, joint pain, or severe allergic reactions are rare but require immediate medical attention.

Should I stop taking my DPP-4 inhibitor if I’m worried?

No. Stopping without medical advice can cause your blood sugar to spike, which carries its own dangers. If you’re concerned, talk to your doctor. They can assess your individual risk, check your health history, and decide if switching to another medication makes sense. Never make changes on your own.

Can I take DPP-4 inhibitors if I’ve had pancreatitis before?

Generally, no. If you’ve had acute pancreatitis in the past, most guidelines recommend avoiding DPP-4 inhibitors. The risk of recurrence is too high. Your doctor should consider alternatives like metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors, or GLP-1 agonists - depending on your overall health and other conditions.

Randall Little

So let me get this straight - we’ve got a class of drugs that increases pancreatitis risk by 13x, yet they’re still on the market because they’re ‘convenient’? Wow. Next they’ll tell us asbestos is fine if it comes in a nice pill form. The real tragedy isn’t the side effect - it’s that we treat diabetes like a software update instead of a biological emergency.

lucy cooke

Oh, darling, this is just the latest chapter in the tragic opera of pharmaceutical capitalism - where convenience trumps catastrophe, and patients become footnotes in a quarterly earnings report. I mean, really - we’ve turned human bodies into A/B test subjects, and the only thing more terrifying than pancreatitis is the silence after the FDA updates the label. 🎭

Adam Vella

While the ROR of 13.2 is statistically significant, it is imperative to contextualize this within the framework of attributable risk and population-level pharmacovigilance. The absolute risk increase of 1 in 834 over 2.4 years is clinically negligible for low-risk populations, and the benefit-risk ratio remains favorable for patients without prior pancreatic pathology or alcohol use disorder. Regulatory labeling is not an indictment - it is a risk stratification tool.

Anny Kaettano

I’ve seen this play out with patients - one woman on sitagliptin came in with pain so bad she couldn’t sit up, and she just thought it was ‘acid reflux again.’ She ended up in ICU. I’m not here to scare anyone, but if you’re on a gliptin and your stomach feels like it’s being eaten from the inside, don’t Google it - call your doctor. You’re not overreacting. Your pancreas is screaming.

Nelly Oruko

so like… if u had pancreatitis before… just dont take these. its not that hard. i know ppl get scared of meds but like… your body tells u stuff. listen. also, metformin still the OG.

Trevor Davis

Look, I get it - big pharma’s got us all conditioned to think ‘no hypoglycemia’ = magic. But if your pancreas is a ticking clock and your doctor’s still pushing gliptins because ‘it’s easy,’ you’re being treated like a spreadsheet. I switched to SGLT2i after my cousin got hospitalized on linagliptin. No more ‘convenience.’ Just survival.

Adam Rivera

My uncle’s been on saxagliptin for 5 years - no issues. But he also doesn’t drink, has zero gallstones, and walks 8K steps a day. Context matters. I’m not saying don’t pay attention - I’m saying don’t panic because of a headline. Talk to your doc, get your labs checked, and if you feel fine? Maybe you’re just one of the 99.9% who don’t get hit.

Rosalee Vanness

Let me tell you something - I used to be the kind of person who took every pill the doctor handed me without blinking. Then my best friend went into the hospital with pancreatitis after being on sitagliptin for a year. She was 42. She didn’t smoke, didn’t drink, didn’t have a history of anything. Just… a pill. And now she’s on insulin, and her life is a different color. I’m not saying don’t take them - I’m saying: don’t take them like they’re candy. Ask why. Ask what else is out there. Ask if you’re really the exception - or just the next statistic they haven’t told you about yet.

Milla Masliy

My doctor switched me from sitagliptin to dapagliflozin last year because of this exact concern. Honestly? Better blood sugar, lost 8 lbs, and zero stomach drama. If you’re on a gliptin and you’re not asking about alternatives, you’re doing yourself a disservice. SGLT2 inhibitors aren’t just ‘new’ - they’re smarter.