Drug Interaction Checker for Acid-Reducing Medications

Check if your acid reducer might interfere with other medications. This tool identifies potential interactions based on the FDA's documented high-risk drugs.

Most people take acid-reducing medications like omeprazole or famotidine for heartburn or stomach ulcers without realizing they might be quietly ruining the effectiveness of other drugs they’re taking. It’s not a rare side effect-it’s a well-documented, widespread problem that affects thousands of people every year. If you’re on a medication for HIV, cancer, or even high blood pressure, and you’re also taking a daily antacid, your body might not be absorbing enough of the drug to work at all.

How Acid-Reducing Medications Work

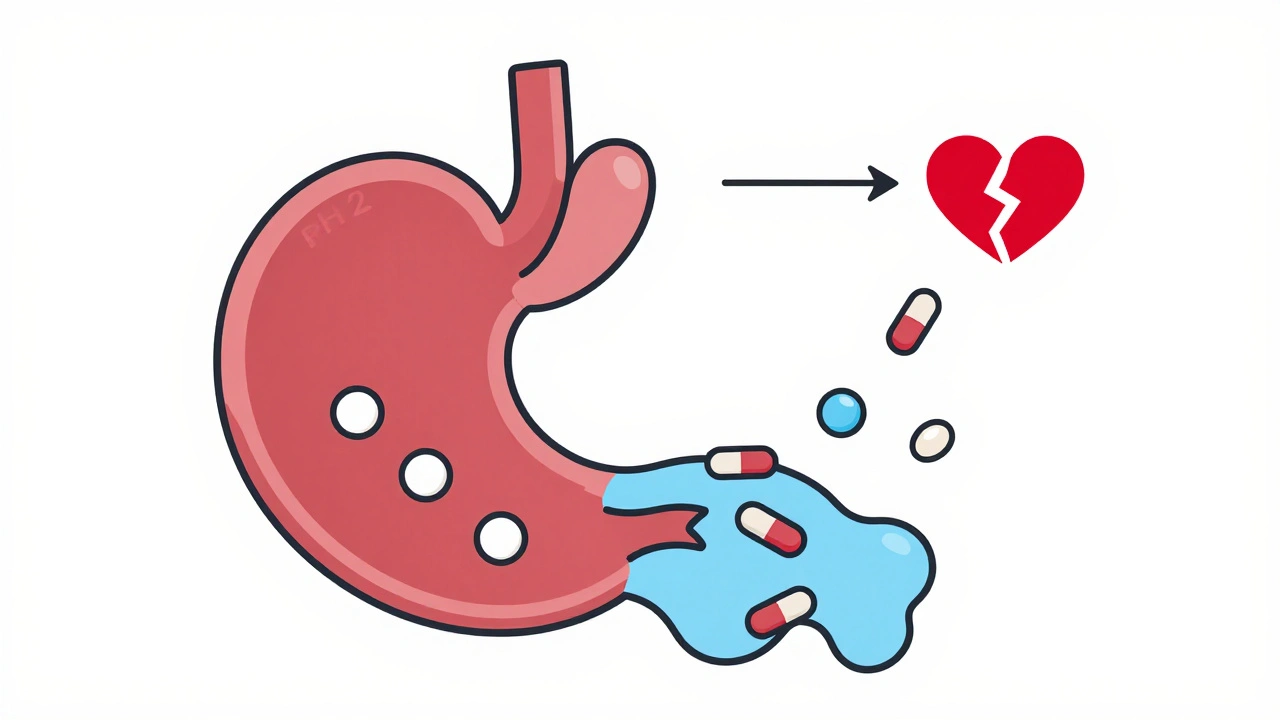

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole, esomeprazole, and lansoprazole, and H2 blockers like ranitidine and famotidine, are designed to lower stomach acid. They do this by either shutting down the acid-producing pumps in stomach cells (PPIs) or blocking the signal that tells cells to make acid (H2 blockers). Normal stomach pH is around 1.5 to 3.5-strong enough to break down food and kill bacteria. When you take these drugs, that pH can rise to 4.0 or even 6.0. Sounds harmless, right? But that small change in acidity can make or break how other medicines work.

The Science Behind the Interference

Most oral drugs are either weak acids or weak bases. Their ability to dissolve and get absorbed depends heavily on the pH of their surroundings. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation explains this: drugs need to be in a non-ionized (uncharged) form to pass through the gut lining. Weak bases-like many antibiotics, antivirals, and cancer drugs-stay dissolved in acid. But when stomach acid is suppressed, they don’t dissolve well. Instead, they sit there, undissolved, and pass through without being absorbed.

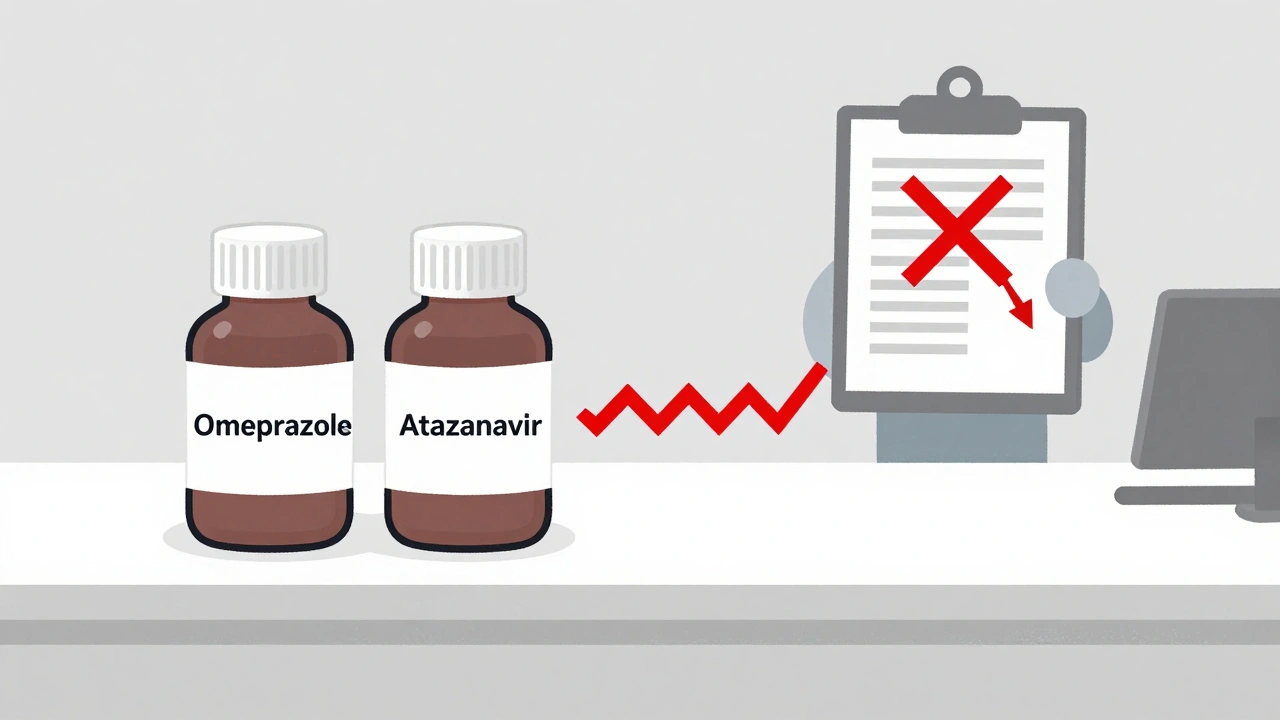

Take atazanavir, an HIV medication. Studies show that when taken with a PPI, its absorption drops by up to 95%. That’s not a small drop-it means the drug isn’t reaching the bloodstream at all. Viral load can spike from undetectable to over 10,000 copies/mL. Patients have reported this exact scenario on forums like Reddit, where one user described their HIV treatment failing after starting Prilosec for heartburn. Their doctor confirmed: this is a textbook interaction.

On the flip side, weak acids like aspirin or ibuprofen can absorb slightly better in less acidic environments. But these changes are usually minor-around 15-25%-and rarely cause problems. The real danger lies with weak bases.

Drugs Most Affected by Acid Reducers

The FDA lists at least 15 high-risk drugs that interact with acid-reducing medications. The worst offenders include:

- Atazanavir (HIV): 74-95% drop in absorption with PPIs. Avoid completely.

- Dasatinib (leukemia): 60% reduction. Dose adjustments or staggered timing may help.

- Ketoconazole (antifungal): 75% drop. Often becomes useless when taken with PPIs.

- Nilotinib (leukemia): 40-50% reduction. Requires careful monitoring.

- My mycophenolate (transplant): Reduced absorption linked to higher rejection rates.

These aren’t theoretical risks. Between 2020 and 2023, the FDA’s adverse event database recorded over 1,200 reports of therapeutic failure tied to these interactions. Atazanavir alone accounted for over 300 of them. In a 2023 study of 12,543 patients, those taking dasatinib with a PPI had a 37% higher chance of treatment failure. That’s not a coincidence-it’s a direct result of poor drug absorption.

PPIs vs. H2 Blockers: Which Is Worse?

Not all acid reducers are created equal. PPIs are far more dangerous when it comes to drug interactions. Why? Because they don’t just lower acid-they keep it low for a long time. A PPI can maintain a stomach pH above 4 for 14 to 18 hours a day. H2 blockers? They work for 8 to 12 hours. That means PPIs create a much longer window where weak bases can’t dissolve properly.

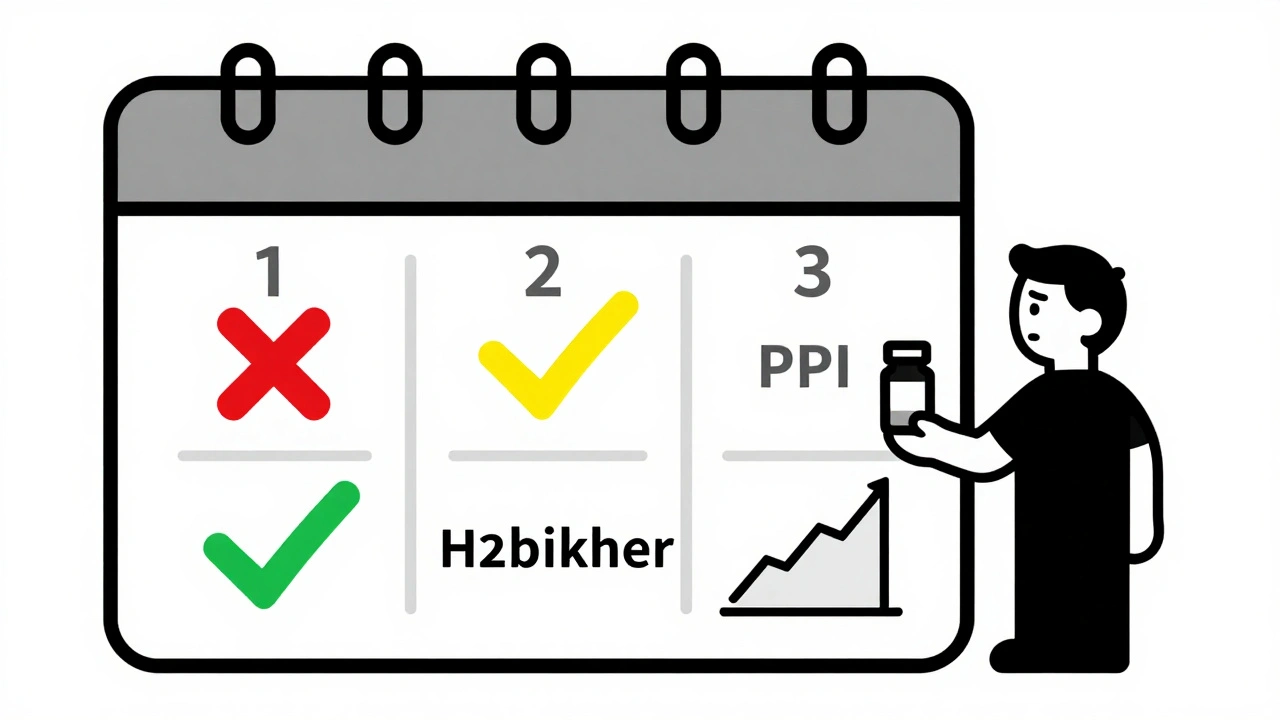

A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open found PPIs reduce absorption of pH-dependent drugs by 40-80%, while H2 blockers only reduce it by 20-40%. So if you have to take an acid reducer and you’re on a sensitive drug, an H2 blocker is the lesser evil. But even that isn’t safe-just less risky.

What About Enteric-Coated Pills?

Many people assume enteric-coated pills-those designed to dissolve in the intestine instead of the stomach-are safe. But that’s not always true. When stomach acid is suppressed, the coating on these pills can dissolve too early. Instead of waiting until the small intestine, the drug releases in the stomach, where it might get destroyed by enzymes or cause irritation. This is especially true for drugs like delayed-release rilpivirine or certain NSAIDs. The result? Unpredictable absorption, unpredictable side effects.

Real-World Consequences

This isn’t just about numbers on a lab report. People are getting sick because their medications aren’t working.

A woman in Ohio reported her blood pressure readings stayed high for months. Her doctor assumed her medication wasn’t strong enough. Only after she mentioned taking Nexium daily did they realize the interaction was causing her antihypertensive drug to be poorly absorbed. Her readings dropped 20 points within days of switching to an H2 blocker.

In another case, a man with chronic myeloid leukemia had his dasatinib dose doubled after his oncologist noticed his white blood cell count rising. He’d started taking omeprazole for acid reflux. When they separated the doses by 12 hours, his response returned to normal. No dose increase needed-just timing.

These aren’t rare stories. Pharmacists in community pharmacies report seeing this pattern weekly. One 2023 study found pharmacist-led medication reviews cut inappropriate ARA co-prescribing by 62% in Medicare patients. That’s proof that awareness saves lives.

What Can You Do?

If you’re taking an acid-reducing medication and another prescription, here’s what to do:

- Check your meds. Look up each drug on Drugs.com or Medscape. Search for “acid reducer interaction.” If it’s flagged, don’t ignore it.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist. Don’t assume they know. Bring your full list-supplements included. Many people don’t realize antacids like Tums or Rolaids can also interfere.

- Consider timing. If you must take both, take the affected drug at least 2 hours before the acid reducer. This isn’t foolproof, but it helps. For atazanavir, even this won’t work-avoid PPIs entirely.

- Ask about alternatives. Is the PPI even necessary? The American College of Gastroenterology says 30-50% of long-term PPI users don’t need them. Deprescribing can reduce risk without losing benefit.

- Use H2 blockers instead. If you need daily acid control, famotidine (Pepcid) is safer than omeprazole for most drug interactions.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA is pushing harder than ever to fix this. In 2023, they updated their guidance to require drug makers to test new medications for pH-dependent absorption issues. Over 37% of new drugs in development now include special coatings or delivery systems to avoid this problem entirely.

Electronic health records now have built-in alerts. If you’re prescribed a PPI while on dasatinib, Epic or Cerner will pop up a warning. Clinicians follow these alerts 78% of the time-up from 45% five years ago.

And new tools are emerging. Google Health’s AI model can predict interaction risks with 89% accuracy. Future apps may scan your medication list and warn you in real time.

The goal? Reduce inappropriate ARA use by 25% by 2027. That could prevent 5,000-7,000 cases of treatment failure every year in the U.S. alone.

Bottom Line

Acid-reducing medications aren’t harmless. They’re powerful tools-but they’re not just for your stomach. They change how your whole body handles drugs. If you’re on a critical medication like an HIV drug, cancer therapy, or immunosuppressant, your acid reducer might be quietly sabotaging your treatment. Don’t assume your doctor knows. Don’t assume your pharmacist checked. Ask. Double-check. And if you’re on a PPI long-term, ask if you even need it. You might be surprised how often the answer is no.

Elliot Barrett

Ugh, another ‘don’t take your meds’ post. I’ve been on omeprazole for 8 years and my HIV meds work fine. Stop fearmongering.

Sabrina Thurn

This is one of the most clinically accurate summaries I’ve seen on Reddit. The Henderson-Hasselbalch explanation is spot-on-especially how weak bases lose ionization in elevated pH. The 95% absorption drop with atazanavir isn’t anecdotal; it’s pharmacokinetic gospel. PharmD here: if you’re on a PPI and any of the listed drugs, consult your clinical pharmacist before making changes. Timing matters, but avoidance is often the only safe path. Also, Tums? Calcium carbonate is a potent acid buffer-same risk as PPIs.

And yes, enteric coatings are a false sense of security. I’ve seen patients with rilpivirine failure because their stomach pH rose enough to trigger premature dissolution. The coating doesn’t ‘know’ when to open-it just dissolves when the pH threshold is crossed. No magic.

Tejas Bubane

Look I’m from India where people take omeprazole like candy with chai. No one checks interactions. My cousin’s uncle took it with his TB meds and got resistant strain. No surprise. This is why western medicine fails in Global South-too much focus on pills, zero on context. You think a doctor in rural UP knows about Henderson-Hasselbalch? Of course not. That’s why people die. Not because the science is wrong. Because the system is broken.

Angela R. Cartes

OMG I took omeprazole with my levothyroxine for 2 years 😭 I thought it was fine because my TSH was ‘normal’… until I read this. Now I’m on famotidine and my energy is back. I’m crying. This needs to be on every pharmacy label. 🥺

Lisa Whitesel

More people should die from this. If you’re too lazy to read your med sheet, you deserve what happens.

Maria Elisha

Wait so Tums counts too? I’ve been popping them like candy since my pregnancy. So my blood pressure meds are basically useless? 😅

Larry Lieberman

🤯 I just checked my med list. I’m on dasatinib AND omeprazole. I’m literally going to the pharmacy right now. Thank you for this. 🙏

Carina M

It is both a moral and scientific failure that this information is not universally disseminated. The pharmaceutical industry’s profit-driven model prioritizes prescription volume over patient safety. The FDA’s tepid response to over 1,200 adverse event reports is not merely bureaucratic negligence-it is complicity. One must ask: how many lives are being sacrificed to maintain the market dominance of PPIs? The answer, tragically, is statistically significant-and entirely avoidable.

William Umstattd

Let me be perfectly clear: if you are taking a proton pump inhibitor while on any antiviral, anticancer, or immunosuppressive agent, you are not just ‘at risk’-you are actively sabotaging your own survival. The data is not ambiguous. The FDA has documented it. The journals have published it. The pharmacists have warned you. And yet, you still take it because it’s ‘convenient.’ This isn’t ignorance. It’s arrogance. And it’s killing people. Every day. In plain sight.

Andrea Beilstein

It’s strange how we treat the body like a machine with isolated parts. We fix one thing-stomach acid-and forget that the whole system is connected. The stomach isn’t just a blender. It’s a gatekeeper. And when we tamper with its chemistry, we don’t just change digestion-we change destiny. Maybe we’re not just treating heartburn. Maybe we’re playing God with molecules we don’t fully understand. And that’s terrifying.

Courtney Black

People think if a pill is FDA-approved, it’s safe. But drugs are designed for populations, not individuals. My dad took PPIs with his transplant meds. He rejected the kidney. They never connected it. Now he’s on dialysis. I don’t blame the doctors. I blame the system that lets this happen. And I blame the people who don’t ask. Because asking is hard. And silence is easier.

Ajit Kumar Singh

India has no such awareness. My uncle took omeprazole with his cancer drug. He died. No one knew. No one cared. Here, we just say ‘beta, thoda sa acid hai, le lo omeprazole.’ No tests. No warnings. No labels. This is why we die young. This is why we don’t trust doctors. Because they don’t know. Or they don’t care. Or they’re too busy. I wish someone had told us. I wish someone had written this. Now it’s too late. 😔